Is it wrong that all I could think of was, how is she 41 and in such a good shape? and also, were those clothes really inside her vagina? But onto more analytical comments…

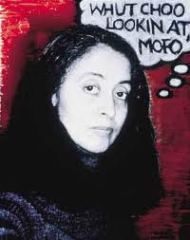

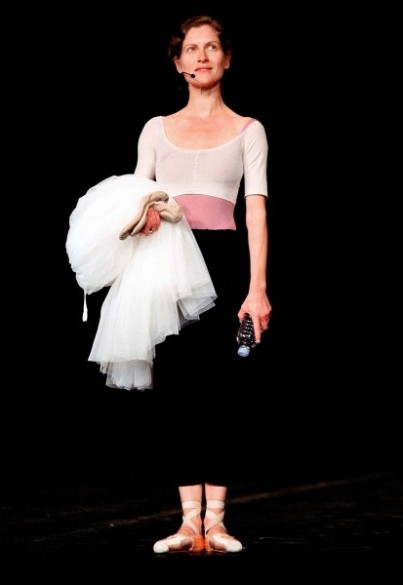

Narcissister is a 41 year old performance artist that wears a Barbie doll face. In her piece, “Every Woman,” Narcissister performs a reverse striptease. She begins the piece naked and proceeds to get dressed from clothes she takes out of her orifices – mouth, vagina, anus, and afro wig – to end the piece fully dressed in see-through spandex. This is an uncomfortable piece to watch. It presents us with a woman that owns her body and takes pleasure in owning it. And this is clear on her body appearance as well. Unlike Marina Abramovic, whose naked body exposes her and shows us a human body, Narcissister’s body is a statement of ownership more than an exposure. Her body is a mannequin in itself, it is her performance. By showing a worked out, thin, tanned, almost impossibly fit body, Narcissister is already telling us she owns her body and does with it what she wants. This is a perfect framing for her reverse striptease.

Narcissister’s “Workout” piece is intense. Here, she puts herself in a work out machine that resembles a static bicycle at a gym, but that is actually a pleasure machine. Involving a black dildo, mannequin hands that reach her breasts, and a wheel with attached straps that slap her in the back, Narcissister’s piece shows us a body capable of self-pleasure and masochism. She is owning her body and her sexuality. She is also commenting on race, with the black dildo and the black afro wig in “Every woman. ”

In Narcissister’s “ass/vag” piece, the performance artist wears a vagina/anus costume and performs a female orgasm. It’s a visually striking piece and my favourite so far. Raw, real, and disturbing, the piece puts on stage female sexuality in its essence. The piece evokes images of cabaret, strip tease, and pornography (notably the back of her costume.)

In “Man-Woman,” Narcissister begins dressed like a man, wearing mannequin like pectorals and a dildo. The piece follows the artist as she wakes up as a man, masturbates to a picture of Narcissister as a woman stuck on the wall, and then becomes the woman of the picture, wearing neon pink pornographic underwear, black skin sleeves and mask, and a bleach blond curly hair wig. She then proceeds to hump the mannequin, clothes, and mask of the initial man persona. This gets even more reversed when, after showing that the dildo representing the man’s penis is not erect any more, Narcissister opens a magazine and masturbates to photos of herself. In the end, she takes the man’s hat and skateboard, and leaves the room. This piece explores gender roles, race, sexuality, and female empowerment. It is disturbingly explicit, pornographic and sexual, but fascinating.

In “Hot lunch,” Narcissiter begins inside a sausage costume as part of a huge hot dog. Once out, she is revealed as a waitress and serves hotdogs which she covers with ketchup and mustard that she squirts from fake breasts. She then strips naked and extracts a red strip in shape of a sausage strip (but also evocative of menstruation and masturbation at the same time) out of her vagina. Finally, she dances and ends the piece inside the bun she began in, naked. This piece is riddling. Her body serves and dominates, but is also consumed. She consumes the body she serves? Interesting.

Narcissister’s work gives credit to her name. She is all about the body; pleasuring her body, selling her body, changing bodies, exploting it, exercising, consuming, masturbating, etc. But the main issue with her body is that is anonymous. We are all narcissiter (“Narcissister is you!”) and we all utilize our bodies for pleasure and commerce. We don’t see her face but we put our face on her mask; we see ourselves riding the bicycle, confronting the dildo, having orgasms, being mixed race. She is bold, but her work reveals the grungy, hidden reality of a world where everything is up for grabs and has a price, including our bodies.

More of her work: http://www.narcissister.com/photos.php

Article in NYTimes: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/17/fashion/the-mannequin-also-speaks-up-close-with-narcissister.html?_r=0